Consider Timothy Agoglia Carey, a rough-hewn, riveting beastie who, starting in the heyday of noir, slouched his way toward some backlot Bethlehem. He first hit a public nerve as a slurry-voiced gunsel in Andre’ de Toth’s B-grade sleeper Crime Wave (54) and was last seen in a trifling part in the trifle Echo Park (86). In between he appeared in nearly four dozen films, ranging from the sublime – a pair of Stanley Kubrick’s earlier and arguably best features – to such artsy turkeys as John Cassavetes’ The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (76).

Usually restricted to playing loathsome genre heavies, Carey’s strongest performances offer the kind of mixed signals associated not so much with art or craft as with pathology or the twisted mysteries of DNA. Paralleling his psycho roles, Carey’s dark personal legend encompasses 40 years of dedicated, or perhaps just helpless, eccentricity – zany behavior shading off into the macabre. Since the era of The Killing (56), Paths of Glory (57), Kazan’s East of Eden (55), and Brando’s One-Eyed Jacks (61), he’d hung in my mind as one of the first Method character actors, embodying all the follies and fevers of that holy-roller theatrical regimen. Even in throwaway parts – opposite The Monkees in Head (68), for Chrissake – you could look into his hooded, jittery eyes and sense real danger. Prankster or madman? Crusader or wise guy? The choice was hard to make when, in the dog days of August 1992, Carey materialized after almost a decade off-screen for an evening of manic schtick and pitiless self-revelation at the Nuart Theatre in West L.A.

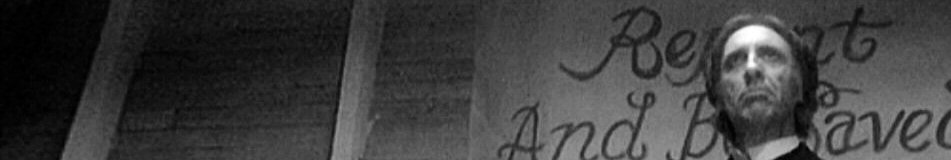

A program highlight was a screening of The World’s Greatest Sinner, possibly the most bizarre vanity-cum-auteur vehicle on record. the 77-minute black-and-white feature credits Carey as star, writer, producer, director, and distributor. He plays a bored insurance salesman who changes his name to God, develops a youth following and a nasty lust for power, and winds up believing his own con. In the end, he blasphemously challenges the heavenly powers and, I think, realizes the enormity of his hubris. (Make that His hubris).

Finally released in 1964, the picture never found its rightful place in the grind houses and drive-ins of the period, where Carey was at the time being hissed by millions in the exploitation hits Mermaids of Tiburon (a.k.a. Aqua Sex)(62) and Poor White Trash (61). This one-night-only screening was the fifth commercial play date for Carey’s brainchild. At the intermission, the long-legged Carey, wearing his sparkly Sinner getup, loped onto the stage, his big-time weirdo persona ingrained and ageless. His voice was like a meat grinder full of nails. He began speaking about the joys of public farting. In a sort of jive disquisition, he cited Salvador Dali on the benefits of breaking wind as a social activity. “Me, I fart loud – I can’t be a hypocrite. I get these parts, but I never get to play ’em because I fart out loud. Why can’t we all fart together? Let thy arse make wind!” […]

Applause at the end faded quickly. Carey took up a position in the lobby, wearing a fixed smile, ready to sign autographs. But the audience filed silently past him. I walked by close enough to see that he believed his own blather. You could tell he was somewhat twisted in the melon, but not plain gaga – a primitive artist and a primitive human.

Back in the Fifties and Sixties, I’d gone to movies because Jack Elam was in them, or Neville Brand – or Timothy Carey. Perhaps only the camera truly loved these kinds of mavericks and marginals, but I’d always regarded the skull-faced Carey as one of the quintessential hard-boiled actors, and I now found myself savoring his mix of gaucherie and ballsiness in taking on, among others, the sensitivity police of the Nineties. As he held his smile and we made passing eye contact, I thought I’d like to pick his lock. For hours afterward, I wondered at Carey’s cockeyed grace in handling the crowd’s rejection, and I dreamed about him that night in his matchless performances – the condemned soldier who kills a cockroach in Paths of Glory, the feral assassin who fondles a puppy and talks mayhem with Sterling Hayden in The Killing.

– Grover Lewis, “Cracked Actor”, Film Comment Jan/Feb 2004; interview conducted in 1992