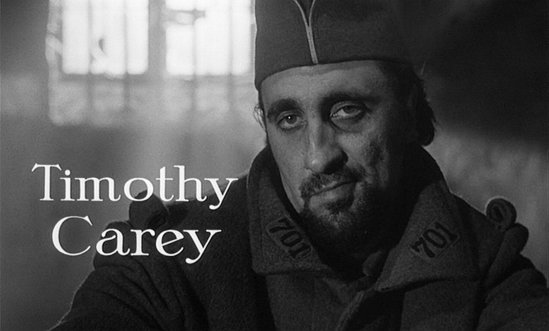

MARON: Now, coming full circle, do you know – are you familiar with Timothy Carey?

GLOVER: Yes! I went to his house – (laughs)

MARON (laughing): I knew it! I knew it!

GLOVER: Yeah, I went to his house in the ’80s, late ’80s.

MARON: Like, is he a role model?

GLOVER: Well, there were two actors when I was studying acting – I could always detect, I could always figure out what the method, for lack of a better word, was that an actor was employing to get to their state. But there were two actors that I did not feel that way about. One of them was Andy Kaufman, and the other was Timothy Carey. And I never met Andy Kaufman, but I had the opportunity to go to Timothy Carey’s house, and it was a very, it was a really – it was really fascinating. I’m very glad I had that experience.

MARON: When I, when I sort of started –

GLOVER: Did you know him?

MARON: No no no, but when I started thinking about you, and about, you know, sort of – not a template but somebody who was within the system and then started to kind of really break away in an extreme way, I thought about Timothy Carey, who I loved in some of the earlier movies; I’m not that familiar with his work, you know –

GLOVER: Well, have you ever seen The World’s Greatest Sinner?

MARON: No.

GLOVER: He directed it.

MARON: Right, right. No, I know about the movie but I’ve not seen it.

GLOVER: It’s worth seeing. I saw it for the first time at his house. He didn’t have it out on DVD at the time and he –

MARON: That’s the one that Zappa did the soundtrack for, correct?

GLOVER: Yes, I believe that’s right, yeah.

MARON: What was your experience with Timothy Carey?

GLOVER: Well, it was fascinating.

MARON: Yeah. You were going there to figure him out, in a way.

GLOVER: Yes.

MARON: How did that happen? How did you get the opportunity to go there?

GLOVER: A friend of mine, Adam Parfrey –

MARON: I know Adam Parfrey, I’ve interviewed him.

GLOVER: Oh you did? OK great, great. Adam –

MARON: It makes sense, it’s all coming together. Apocalypse Culture, the first volume, changed my life. And it seems like you’re kind of symbiotic –

GLOVER: Yeah, he’s a great publisher. He’s in my first film, he’s in What Is It?

MARON: His father was a character actor as well.

GLOVER: That’s right. That’s something he and I have in common. […]

MARON: So he set you up with Timothy?

GLOVER: Well, there was a friend of his, or somebody he was acquainted with, that had been in contact with Timothy Carey, and so that was set up so that the three of us went to Timothy Carey’s house. We were there for a number of hours.

MARON: And what did you glean?

GLOVER: (laughs) Well, um, (laughs) I’m trying to think if it’s right to say, but – (long pause) he was – (laughs) (long pause) (laughs) – the first hour was spent talking, Timothy Carey talked about passing gas, and the health of this –

MARON: Uh huh. For an hour.

GLOVER: Yes. (laughs) And at first of course it was kind of funny, the first 15 or (laughs) 20 minutes it was funny. And then, and then – (MARON laughs) – it was very serious. He wasn’t doing it as a joke. And then it wasn’t really so funny (he and MARON continue to laugh throughout). And then it was kind of funny again. We were there for several hours.

MARON: Well, you watched the film, right?

GLOVER: Eventually – probably about two hours into it. We were at his guest house, which was larger than this and was kind of his studio, and we were out there for most of the time. Then we went into his living room and he showed us the film, which was excellent. It’s a very interesting movie. And then I asked him – what I noticed about him, I went and saw both East of Eden and…

MARON: The Killing?

GLOVER: And The Killing. I think I saw The Killing a little later.

MARON: Paths of Glory?

GLOVER: Paths of Glory I saw later. But I noticed when I was watching the films [Ed. note: The other film must have been One-Eyed Jacks]– you know, James Dean is one of those actors that you’re studying as a young actor, and Marlon Brando – but in those scenes, Timothy Carey has fight scenes with both of them in bars. But in those scenes, my eye was not on James Dean, my eye was not on Marlon Brando, it was on Timothy Carey. But the part that I hesitate to say a little bit but maybe I’ll say it – at one point – you hear a lot of different tales, I don’t know if you’ve heard a lot of tales about Timothy Carey, but I’ve heard a lot of tales about him that are fascinating. Like he disappeared during the shooting of Paths of Glory in Germany. If you look at the film, his character is in shadows at a certain point in the prison. But he wasn’t originally supposed to be in the shadows. He disappeared during the middle of production. I’ve heard different tales as to how he was found, but essentially they just had to hide his character and then they put him back in once he showed back up again. Also I think he met his wife in Germany there, and Kubrick did as well. So there’s something in common. But he kind of pointed at his head at one point and said – I almost feel like I’m betraying something private. He said something about his mental health. So it was fascinating to me because I realized that part of what was hard for me to detect about him was there was something going on, I gleaned or assumed from talking to him, that was essentially undetectable because he was having, for lack of a better word, mental health issues. And so that’s part of why I would say probably it was hard for me to detect what his specific method was. Like Marlon Brando, he’s a great actor but I can essentially understand what he’s employing to get to the state, or James Dean. But like I said, I never met Andy Kaufman so I don’t know exactly where it was coming from. And Timothy Carey, even having had that meeting of course, I don’t know the exact neurons, so to speak, for getting to that point.

MARON: Well, you’re sort of one of those guys too.

GLOVER: Well, I probably early on have always been interested in the idea of art and madness, for the lack of a better word, as being good for art.

Crispin Glover – WTF Podcast with Marc Maron #673 (01.18.16)